(Page 38)

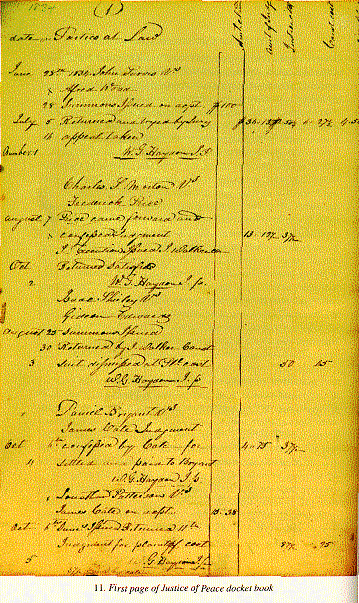

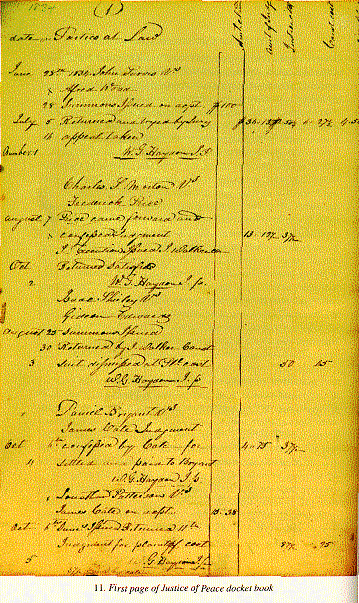

The Justice of the Peace

Docket Book

The proceedings before the Whitley Point Justices of the Peace were predominantly

civil in character--with one or more private plaintiffs seeking damages from one or

more private defendants. The vast majority of these civil cases

were common law actions

falling into two categories: actions on account, and actions on a note.

An action on an account was a subspecies of actions of debt or assumpsit (indebitatis

assumpsit), founded on an express or implied contract,

for services performed or

property sold and delivered. The term "account" referred to the relationship between

the parties; and the action existed to avoid the need for a multiplicity of suits for

multiple transactions. Thus, purchases from a store on

credit might give rise to

a suit to recover the balance owing on the account. (86)

The early such actions recorded by Justice Haydon were noted as actions "on acpt.,"

or sometimes "on acct." (87) Later, the actions are recorded as "on account." However, "acpt." (88) did not seem to be a proper contraction of the word "account." Then I came

to

an action brought on December 28, 1839, by Ephraigm Marckel, labeled as "on accounpt." (89)

This entry, although misspelled, suggested an answer. The "on acpt." actions apparently

represented contractio

ns of the French "acompte"--in English, "account." The English common law terminology in "law French," a consequence of the Norman conquest,

had carried over into colonial common law usage and found its way into the language

of commercial practice and d

ispute resolution in frontier Illinois.

Not surprisingly, some of the actions brought on account appear to be brought by business

enterprises--the storekeepers or tavern operators of Whitley Point and the nearby

villages. Thus, for example, sev

eral actions are brought by Charles W. Nabb, or Nabb "and son." (90) Others are brought by "Martin Elder & Co." or "Elder & Dasey." (91) Others,

however, are brought by individual proprietors.

Actions on account were not limited to claims to enforce payments for sales of goods.

Amos Waggoner (later himself a justice

(Page 39)

and store keeper) on March 19, 1839, brought

an action against James Cate "on acpt." for $13.50 "for work done and received as per bill filed." (92) Waggoner prevailed in his suit, thus obtaining payment

for his labors,

whatever they were. Later the County Commissioners brought suit against several individuals

"on acpt." for not working on the roads, as all householders were obligated to do several days each year. (93) In another case, the firm of Solomon & Chaplain brought

suit "on acpt." against an individual for $20 damages "for trespass," which would

seem to stretch the notion of an action on account; but the plaintiff

prevailed. (94)

The other major category of civil actions was suits brought on notes. The record provides

few details, but occasionally actions were brought on both a note and an account, (95)

which suggests that a purchaser may have run up an account and then given a note

for all or part of the unpaid balance. Other suits on notes no doubt reflect purchases

with notes given as evidence of obligations to pay. Also,

there is every reason to

believe that notes were signed in the absence of purchases, as a way to borrow money

and assure its repayment. Without banks or other institutional sources of credit (not

to mention credit cards), one may reasonably assume tha

t those in need of cash would

frequently borrow from their more liquid neighbors, who were willing to oblige in

return for adequate interest.

Interest rates were spelled out in the notes and were not ignored by either the plaintiffs

in seeking

relief or the justices in awarding it. Interest was frequently specified

in the claim for relief, and the rates were not low. The prevailing rate in 1837, for example, seems to have been 12%. (96)

<

BR>

A curiosity of commercial practice at the time is that an unusually large number of

notes were written to come due on Christmas Day--December 25. (97) This has been explained

by Professor David H. F

ischer as a cultural transmission via Virginia from southern

England, where "cultural time" was "regulated by the Christian calendar," and accounts

were traditionally settled on Christmas Day and other religious holidays. (98)

Following a trial on an account or a note, if the losing defendant did not promptly

pay the judgment, the successful plaintiff was entitled to a writ of execution, which

the justice issued to the constable

(Page 40)

directing him to seize the goods and chattels

of the defendant and sell them as necessary to pay the judgment. Frequently the defendant

would pay up, and the execution would be returned "satisfied." However, occasionally

an execution would be returned

"no property," (99) or the defendant himself could not be found. (100)

For the first six years of the docket book--from 1834 to 1840--successful

plaintiffs

faced with a return of "no property" were simply out of luck. Then in 1840 plantiff

George Munson brought an action on a note for $68.46 against Joseph Duncan, the defendant. The defendant was brought before the justice and, after trial, jud

gment was awarded

the plaintiff. But the constable could find no property belonging to Duncan.

At that point Munson took advantage of the Illinois Act Concerning Attachments. (101)

The Act per

mitted a justice in certain circumstances to issue an attachment against

the property of the debtor. Here the debtor, Duncan, apparently had no real or personal

property. But Munson believed that various third parties owed Duncan different amounts--and

Duncan's entitlement to these amounts was a kind of property. The way to reach this

property interest was to serve a process known as garnishment on the third-party

debtors of Duncan, and require that they pay their debts not to Duncan but to Munson. M

unson (or his attorney) thus caused Justice of the Peace Waggoner to issue summons

to several third-party debtors--John Kennedy, Thomas Randol, James Poor, William Miller, Richmond Webb, and others--directing them to appear in court.

When these

third-party debtors appeared, judgment was given against them in favor

of Munson. The plaintiff was thus happy. And the justice and constable presumably

were delighted, because they charged additional fees for issuance and service of

the garnishments a

nd executions. (102) Indeed, the total costs of $20.20 (103) amounted to a significant

percentage of the original debt of $68.46. This would have been o

f little concern

to the successful plaintiff as the costs were paid out of the proceeds of the garnishments--i.e., out of the defendant Duncan's property.

Eight years later, in 1848, Joel H. Munson, no doubt a relative of George, used this

sam

e complex procedure to try to collect a debt owed to him by Martin Walker. (104)

(Page 41)

In addition to contract actions brought on accounts or on notes, a much smaller number

of actions were brought to obtain damages for tortious conduct. Thus, in April 1837

William Waggoner brought an action against Samuel Pugh for "trespassing threats et

c.

Rioting etc etc etc." Waggoner prevailed, obtaining a judgment for $3.00. (105) A year

later, Elisha Linder brought an action against Philip Apple "sounding in Damages

Trover & Conversion." Appa

rently Linder believed the defendant had taken his property.

The case was "settled by parties." (106)

Several actions were brought for "trespass." (132) In one of these, Thomas Currey sued

Garland Sims for cutting down his timber. After the parties met and a witness was

called, the matter was settled.

The Justice of the Peace Act (107) contained a remarkably modern-sounding provision providing

for arbitration of disputes if the parties so chose. (108) In "all" cases before a justice,

the parties might "refer the difference between t

hem to arbitrators, mutually chosen by them." The arbitrators would then "examine the matter" and "make out their

award in writing, and deliver the same to the justice, who shall enter the said award

on his docket and give judgment according thereto." T

he Act provided that such matters could be referred to "arbitrators," using the plural, although presumably the

parties might agree to use a single arbitrator. Interestingly, the justice presented

with an arbitrators' award had no discretion to review i

t, but was instead directed

to "give judgment according thereto."

This arbitration procedure was used, although infrequently, by the citizens of Whitley

Point. In an early case brought in 1835 by I. Waggoner--presumably Isaac, the patriarch

of

the early settler family--against Noah Webb, Isaac's son-in-law, (109) an "action

[on] acpt.," the matter was summarily reported as "settled by arbitration."

Four years later, in 1839 the arbit

ration procedure was used in what appears to have

been a more complex matter. (111) Samuel Hughes brought suit against three presumably

related parties: James G. Green, Thomas P. Green, and William Gree

n. The suit was

brought on a note, and plaintiff alleged that one or more Greens owed Hughes $52.50. The

parties agreed to arbitrate and chose two arbitrators--Harman Smith and Israel Ellis--which

meant the judgment had to be unanimous. After "hearing

the parties and examining

(Page 42)

the papers," the arbitrators ruled on July 27, 1839, in favor of the plaintiff, Hughes.

The two arbitrators were each allowed $1.00 for their services.

Two days later, on July 29, Hughes then brought a separate suit against just one of

the Gre

ens--James G. Green--to enforce the arbitrators' award. Green failed to appear

at the appointed time, so judgment was given in favor of Hughes--but for only $46.12-1/2.

The record then indicates that Green obtained a copy of the judgment, and that on

N

ovember 12, 1839, the execution was "stoped by supersedy"--i.e., by an appeal from

the judgment of the justice (based on the arbitrators' award) to the Circuit Court

for Shelby County. The procedure by which such an appeal might be taken was to obtain a

copy

of the judgment, take it to the clerk of the court, and enter into a bond sufficient

to cover the judgment and costs. Upon the execution of the bond, the clerk would

issue a supersedeas "enjoining the justice and constable from proceeding

any further in said suit." (112) The appeal having been taken, we read no more of the case.

Although most of the cases tried by the justices were civil, there were enough criminal

cases to make

it clear that life on the frontier had its rougher aspects.

The first criminal case to appear on the docket of Justice Haydon took place in 1838.

Under Illinois law, a criminal case could be instituted either "upon the knowledge

of any justice

of the peace, or information of any person upon oath." (113) In either

case, the justice would issue a warrant to the constable directing him to arrest the person

charged. The constable would then summo

n six jurors to hear the evidence. Thus, the

justice served a law enforcement as well as judicial function.

On December 11, 1838, Justice Haydon issued a warrant for the arrest of Peter Harmon

and John Brown. (114) The nature of their offence was not specified, although based

on what happened later it appears they had been fighting. In any event, a jury was

impanelled. The jury heard the evidence, retired, and brought in a verdict of guilty,

fining

Harmon and Brown $7.50 and costs.

Immediately after the verdict, Brown and Harmon apparently resumed their disagreement,

because Brown sued Harmon in an action "for keeping the Peace," and Justice Haydon

issued a "peace

(Page 43)

warrant," which was immediately executed by the constable. The matter

was resolved when "the parties made it up." The post-verdict activity by the two squabblers

cost them together $1.00 in costs--75 cents for Justice Haydon, and 25 cents for Constable

Walker.

In 1839 there occurred another criminal proceeding which is interesting in part because

of the likely relations between the person initiating the case and one of the defendants.

On April 29, "William Henricks made oath" before Justice

Haydon "that John Stricklin and Wm. B. Henricks was guilty of affray on 28th April." (115) William, the initiator

of the proceeding, with no middle initial, may have been the father of the defendant,

"W

illiam B." Justice Haydon issued subpoenas which were returned on the 29th, a jury was impanelled, witnesses were heard, and the jury found both parties guilty,

fining Stricklin $5.41 and Henricks (or Hendricks) $3.66, and assessing costs.

Less

than two months later, Parmel Hamilton made oath before Justice Haydon that on

July 8, 1839, three local worthies--Pleasant Dodson, Samuel Martin and John Goldsby--did,

"in the Town of East Nelson in a tumultuous manner...commit a Riot by threatening

&c." (116) As already pointed out (supra, p. 25), East Nelson was a small settlement a

few miles north and west of Whitley Point. Two days after the alleged riot, the proceedings

were initiate

d before Justice Haydon; and based on Hamilton's oath, the justice issued a summons directing the alleged wrongdoers to appear before him eight days later,

on July 18, 1839. On that day the three defendants were brought into court. Apparently

no jury de

mand was made; and the judge heard the evidence and found for the defendants, who were discharged.

More serious matters, including felony charges, were reserved by statute to the Circuit Courts. (117) Thus, when Philip Armantrout was charged with an unspecified felony in

August 1839, he was bound over to appear at the next term of the Circuit Court. (118)

Another serious case arose on

May 12, 1840, when one Townson Womack appeared before

Justice Amos Waggoner, who had by now succeeded Justice Haydon. Womack swore that

he feared Peter Harmon--who had been fined two years earlier for fighting--"will beat

wound or kill him or his wife." (119) Given the limited jurisdiction of a Justice of the Peace,

Waggoner could not try Harmon for the alleged offense. But he could and did issue

a warrant for Harmon's arrest;

(Page 44)

and he issued subpoenas for witnesses--S.N. Montague,

J. Poos and Esther Womack, perhaps Townson's wife. Harmon was brought in the same day,

evidence was heard, and the case against Harmon was sufficiently strong that he was

required to "enter into a r

ecognizance with sufficient security in the sum of $100

for his appearance" before the Circuit Court in Shelbyville. In the meantime, Harmon was

ordered to "keep the peace Especially toward the said Townson Womack & his wife."

Justice Waggoner asse

ssed costs of $4.433 4 against the defendant Harmon.

Other instances of fighting or unruly behavior resulted in proceedings before Justice

Waggoner. Thus, in September 1840, Alfred Gaines was charged with "disturbing the

peace of the people of

Nelson &c." He was found not guilty.

Not so fortunate were John J. Haydon (a son of the previous justice) and William Easton,

who had the misfortune on February 5, 1841, to be spotted by Justice Waggoner while

"engaged in the act of personal fighting." (120) Justice Waggoner promptly issued a

warrant, ordered the two malefactors brought in, charged them, tried them, and--having

caught them in the act--found them guilty and fined them each

$3.00 and costs. Haydon

paid but execution had to be issued against William Easton to recover his fine.

The Eastons were a boisterous family. On the same day that Justice Waggoner saw the

fight between Haydon and William Easton--Februar

y 5, 1841--Andrew Gamill testified

that he saw James Easton "at the House of H.S. Appels draw a knife with intent to

do a boddily injury to some person there present and that the said James Easton did advance

toward a crowd of persons with the k

nife drawn and said that he would cut throats." (121)

Justice Waggoner issued a warrant for the arrest of James Easton, and the matter

was turned over to the Circuit Court for trial.

Later that

year, on June 30, 1841, James Easton was charged as a result of another

brawl. This time Anthony W. Debrewler caused a peace warrant to be issued "against

the Boddys of James Easton and John Owens." (122)<

/A> Apparently Owens was discharged after

a hearing; but the next day--July 1, 1841--Debrewler obtained another peace warrant against

Easton "for threats and &c." After the hearing, Easton was discharged.

(Page 45)

Shortly thereafter Debrewler found himself on the other side of the law when, in August

1841, Ebenezer Noyes charged him with "an abuse of the Estray Law." (123) Possibly he

had failed to record finding

one of Noyes' farm animals. In any event he was found

guilty and fined $0.37-1/2 and costs, which were more substantial--$2.62-1/2. Noyes also

brought a civil action against Debrewler "for damages $1.50," which was transferred

for trial to another justice. (124)

Noyes and Debrewler were plainly not on the best of terms. One month after the estray

dispute, Noyes caused a criminal proceeding to be initiated against Debrewler alleging

that the

latter "is a leeding an idle Life & not having Wherewith all to maintain himself & family." (125) Noyes obtained from Justice Waggoner a "vagrant warrant" "against

the Boddy of the said A. Debre

wler." However, after a jury trial, Debrewler was acquitted.

Women were by no means exempt from the force of frontier justice. One case was initiated

on a charge by John North against Patrick and Elizabeth Cook "for the Braking open

of a door o

f smoke house and taking there from a spinning wheel &c other articles

&c." (126) A warrant was issued, and the matter was referred to the Circuit Court.

Nor were youngsters immune from

the discipline of the law. The writer is chagrined

to report that on August 8, 1843, a few months after Moultrie County was established

as a separate county, William Snyder obtained a warrant for the arrest of "William

Martin, Charles Martin & Marr

y M. Martin for an assault & battery committed on the person

of Henry & William Snyder on the 6th Instant at the town of Nelson." (127) Two of the

defendants were brought into custody, "and at t

he request of the said defendants'

father a Jury Warrant is issued." The 1850 United States Census lists a head of household,

Lewis Martin, 44, who had moved to Illinois from Indiana a few years before, with

a daughter, Mary M., 18. In 1843, Mary M. wo

uld have been only 11. Perhaps the other

two defendants were older brothers (not listed in the 1850 census). In any event, the

jury found the youngsters not guilty.

In addition to his duties with respect to the trial of civil and criminal case

s as

described above, a justice was given significant responsibilities under the Illinois

Act To Provide for the Maintenance of

(Page 46)

Illegitimate Children. (128) Upon complaint by

"any unmarried woman, who shall be pregnant or delivered of a child, which by law would

be deemed a bastard," the justice was directed by the Act to issue a warrant for

the arre

st of the person identified as the father:

Upon his appearance, it shall be the duty of said justice or justices, to examine

the said woman, upon oath or affirmation, in the presence of the man alleged to be

the father of the child, touching the charge against him. (129)

Following this hearing it was the justice's duty to decide whether to bind the accused

father over to the next Circuit Court, with sufficient recognizance bond to secure

his appearance. If the accused father refused or was unable to provide bond, he was

to be committed to jail to await the next term of the Circuit Court.

The Circuit Court would then decide, after jury trial, whether the accused was the

"father of the child." If the answer was affirmative, "he shall be condemned by the

judgme

nt of the said court, to pay such sum of money, not exceeding fifty dollars,

yearly, for seven years, as in the discretion of the said court may seem just and necessary

for the support, maintenance, and education of such child." <

FONT SIZE="-2"> (130) However, the Act,

in a decidedly unmodern provision, provided that the "condemned" father could avoid

his support obligation by offering to take custody of his child. Specifically, the Act

provided that the father

shall be permitted to take charge and have the control of his said child; and from

the time of the said father taking charge of such child, or should the mother refuse

to surrender the said child, when so demanded by the said father, then and from thenc

eforth the said father shall be released and discharged from the payment of all such

sums...for the support, maintenance, and education of any such child.

Two proceedings under the Illegitimate Children Act are recorded in the Whitley Point

judicial record. The first, in November 1841, was initiated on complaint by Patsy

Waggoner, probably a niece of Justice Waggoner, against Benjam

in Freeman. (131) The

docket provides no other details. The other was initiated in April 1844 by complaint of Rhewann

[?] Fleming naming William L. Ward as the father of her child. (132

) Justice Waggoner

issued the requested warrant against "the boddy of the said William L. Ward." Whether or not he was "condemned" to support the child is not disclosed.

(Page 47)

|