(Page 48)

4

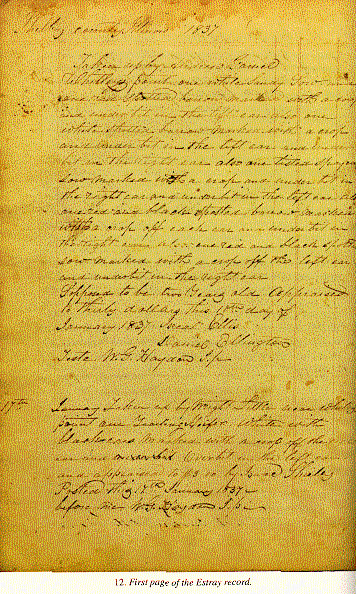

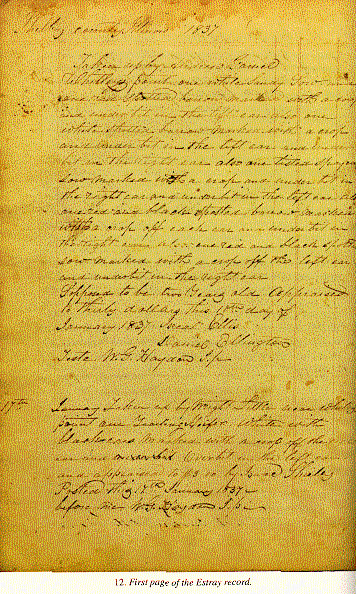

The Estray Record

Because the economic basis of the Whitley Point community was agricultural, not surprisingly

much of the accumulated wealth was in the form of farm animals. The general practice

in Illinois was to permit livestock to roam the prai

ries and timber, with the result that fences were intended to protect the crops from the livestock or scavengers

rather than to enclose the animals.* Accordingly, it was far more important than

in a closed or fenced environment for

* In Illinois, unlike most states in which both pasture land and tillable land were owned by individual farmers, the Supreme Court early ruled that the prairies would be held in common for pasture land. The leading case was Seeley v. Pe

ters, 10 Ill. 130 (1848), in which the defendant's hogs had broken into a field owned by plaintiff and damaged certain crops. When plaintiff sued, the defendant argued that the field was badly fenced. (In the Illinois Supreme Court, plaintiff was repr

esented by William H. Herndon, later one of the partners in the Springfield firm of Lincoln & Herndon.) The fundamental issue was whether a landowner was obligated to enclose his land with a fence if he wanted to protect it against the depradations of cat

tle or hogs. The Illinois Supreme Court ruled that although English common law did not require the owner to fence his property if he wished to protect it, that principle was inapplicable to the conditions of Illinois, which was found to be "unlike any oth

er of the Eastern States" because "from the scarcity of timber, it must be many years yet before our extensive prairies can be fended." Illinois custom was "for the owners of stock to suffer them to run at large. Settlers have located themselves continguo

us to prairies for the very purpose of getting the benefit of the range. The right of all to pasture their cattle upon uninclosed ground is universally conceded." (10 Ill. at 142.) This custom, according to the Court, had been embodied in Illinois statute

s governing "inclosures." Thus, farmers could safely permit their cattle to run at large; and the owners of the fields were bound to fence against them.

The rule of Seeley v. Peters continued for years to be applied to "outside" fences until it was finally changed by statute. (See 19 Ill. Law Rev. 354.) As a result, farmers allowed their stock to wander freely and fenced their crops to keep out the

ir own and their neighbors' animals. In effect, the stock were fenced out rather than fenced in. This is said to have increased the costs of fencing and delayed the clearing and cultivation of prairie land. (Smith, History of Macon County, Illinois, Fr

om Its Organization To 1876, pp. 29-30.)

(Page 49)

farmers to mark or brand their animals; and

it was equally important for the law to provide standards and procedures to govern the situations

where roaming animals might break into a fenced area of crops, to provide a practical

way for owners to identi

fy and recover their animals, and to govern the respective rights of owners and finders.

An Englishman, William Oliver, in a book written to enlighten people in England interested

in emigrating to the American frontier, (133) described the livestock owned by farmers

in central Illinois at the time. Illinois horses, Oliver wrote, were "mostly small, bare-legged, durable animals, and more adapted for the saddle than for the heavier

kinds of agricultural labour." (134)

Due in part to the largely unenclosed character of the land, cattle were mixed breeds.

"Bulls of all shapes, colours, and dimensions are going at l

arge...." (135) Owing to

their wild state, cows did not calve regularly; calves were frequently born during

the winter, when they might die or have the tips of their ears frozen off--a phenomenon

reflected in a few of the Wh

itley Point estray descriptions. (136) Calves which survived

were kept in small fenced enclosures "as an inducement for the cows to come home." (137)

D

uring severe weather some farmers would feed their cattle corn stalks or husks; but

many allowed their animals to shift for themselves. The cattle viewed by Oliver were

small but hardy, and were generally ready at three years age to be sold to drovers w

ho would take them east to Ohio to be fattened before being conveyed to their final destinations

in eastern markets. (138)

Oliver thought highly of hogs. "There is," he wrote, "perhaps, no other

animal which

the western farmer possesses, reared with so little trouble and expense, and which,

at the same time, adds so largely to his comforts, as the hog." (139) The hogs were

allowed to roam at

will, generally "luxuriating amidst a great abundance of mast, consisting

of acorns, hiccory nuts, walnuts, [and] hazel nuts"--except "when put up to get corn."

Oliver found that pork fed in this way was "the sweetest I ever taste

d." (140) Despite this advantage, he also found that the breed of hogs was bad: "they are long-nosed,

thin creatures, with legs like greyhounds," and "they think nothing of galloping

a mile at a heat, or of clearing fences wh

ich a more civilized hog would never attempt." (141) Invited to a hog-killing, Oliver unsympathetically noted that the putative victims

were "very wild and savage,

(Page 50)

any uproar or squealing mak[ing] them so outrageous,

that they become quite unmanageable." (142)

Oliver found few sheep, the ones he saw being "nondescript," but bearing some of the

marks of th

e merino--for example, "the tufted crown." (143) Although receiving "little

care," they grew to a "considerable size"--"some from fifty to seventy pounds." The

sheep were kept solely for their wool, mut

ton being "never seen at table," except in the

house of "some person from the old country." (144)

The earliest estray entries in the Whitley Point Record Book were made in January

1837. At that

time the governing law was An Act Concerning Estrays, enacted by the

Illinois legislature in February 1835. (145)

The basic principle of the 1835 Illinois Estray Act--consistent with the notion

that

the prairies were common pasture land--was that strays should be allowed to run loose

until found by their owners. Finders were permitted to take possession of strays

only if the finder "takes up" the animal at his own farm or residence. The law

also provided

that no person shall be allowed to "take up" any cattle, sheep, hog or goat between

the months of April and the first of November unless the animal was "found in the

lawful fence or inclosure of the taker up, having broken in the same."

The 1835 Act required any person who "takes up" any stray horse, mare or colt, mule

or ass, to take the animal before a justice and make oath that he "took up" the animal

at his "plantation or place of residence," and that the marks or brands ha

d not been

altered since the taking up. Persons taking up strays at any place other than their

farm or residence were subject to a fine of $10 and costs, or to a jail term. After

the stray horse or mule had been taken before the justice, he would then

issue a

warrant directing three "housekeepers" to appraise the animal. The appraisal and a description

of the animal would be entered in a book to be kept by the justice, and transmitted

to the clerk of the County Commissioners Court within 15 days.

The prescribed procedures differed for cows, sheep, hogs and goats, which could less

easily be taken to the justice's place of business than a horse or mule. The law

provided that anyone finding a "head of neat cattle, sheep, hog or goat," was di

rected

to take the animal not to a justice, but to some other housekeeper, who would then

(Page 51)

go

with the finder before a justice and make an oath similar to that required for the

horse or mule. Again, the appraisal and description of the animal would be entered

in the justice's record book and transmitted to the clerk. However, if the appraise

d value

of the cow, sheep, hog or goat was not in excess of $5, then the justice did not

have to so inform the clerk, but would enter the value and description in his own

estray book.

Finders were entitled to rewards from the owners--$1.00 for

a horse, mare, colt, or

mule; 50 cents for each head of cattle; and 25 cents for a hog, sheep or goat. Finders

were also entitled to "all reasonable charges."

If no owner appeared within one year to prove his ownership, the rights to the stra

y

animal would be vested in the "taker up." But at any time thereafter, the former

owner (except in the case of cattle, sheep, hogs or goats worth less than $5 per

head) could prove his ownership and "recover the valuation money, upon payment of costs

and

all reasonable charges." In the case of such animals worth less than $5, after one

year a former owner was simply out of luck.

The Whitley Point estray record, which stretches over the period from early 1837 to

1855, is informative about t

he kind of farm animals kept by central Illinois farmers

and about the ranges of values of those animals. Hogs, cattle, and sheep predominate,

with values varying depending on age, condition and other factors.

During the period covered by the r

ecord, cattle tended to be valued in the range of

$5 to $10, although a 4-year old black steer found in 1853 was appraised at $20.50. (146)

Hogs were worth less, generally in the range of $1 to $5. Shee

p, which were less

frequently reported, ranged from 75 cents to $1.50.*

Horses were the most valuable animals. A bay filly with a blaze in the forehead and

supposed to be two years old was appraised in 1840

* The appraisals for estray law purposes appear low in relation to tax appraisal values, which may themselves have been low in relation to fair market values. An early property tax assessment for Moultrie County, for 1858, reports that in

the entire county there were 17,902 hogs valued at $38,285 (average value for tax purposes, $2.14), 7,918 cattle valued at $103,395 (average about $13.00), 7,795 sheep valued at $11,712 (average $1.50), and 2,997 horses valued at $162,324 (average $54). (

Combined History, p. 72.)

(Page 52)

to be worth $15. Two years later,

another bay filly, three years old, was found to be worth $35. And a brown pony about

13-1/2 hands high and 12 years old, was thought to be worth $13.50. (147)

The Illinois Estray Act required that appraisals be performed by "disinterested housekeepers." (148)

Whether the appraisers and finder were separate "housekeepers," and whether the appraisers

were in f

act "disinterested," may both be questioned. For example, Nathan Womack twice appraised steers found by Abner Womack; (149) Andrew Scott appraised

a heifer found by William Scott;

(150) B.H. Siler (151) appraised a steer yearling found

by B.W. Siler; Samuel Munson appraised another steer yearling taken up by Joel H.

Munson; (152) and John W. Edwards appraised a small brown steer for Gideon Edwards (153) and

later appraised three sows for the same relative. (154)

In looking for information about the Martins I found that in January 1845, James Martin

of Lynn Creek found a heifer which was appraised for him by John Martin, who was

probably his brother. (

155) Their uncle, William Harvey Martin, "Uncle Billy" the Baptist

preacher who lived on Lynn Creek, found a heifer in 1853 which was appraised by "Wm H. Martin son." (156) This could be a ref

erence simply to an unidentified son, but that

seems unlikely given the otherwise general practice of naming the appraisers. More

likely it is a reference to a son of "Uncle Billy" also named William Harvey Martin. And

in fact we know that the senior W

illiam H. did name one of his sons William Harvey. (157)

Also, in 1850 Jane Martin took up a heifer that was appraised by William H. Martin. (158)

<

BR>

In November 1840, Charles N. Martin found a steer which was appraised by William and

John Martin. (159) And a month later William Martin "of Linn Creek" found a steer which

was appraised for him by

Thomas M. and Charles N. Martin. (160) The precise details

of these relationships are not clear and, in any event, would be of interest only to their

descendants; but the general pattern is noteworthy f

or the relaxed attitude it demonstrates

toward the requirements of the Estray Act that appraisals be performed by separate "housekeepers" who were in fact "disinterested."

(Page 53)

|